Mandelbrot Test Code¶

Choosing a good number of blocks and threads per block is an important part of CUDA Programming. To illustrate this, we will take a look at a program that generates images of the Mandelbrot set. To run the programs you will need a CUDA capable machine as well as the appropriate XOrg developer package (X11 is likely installed on your linux machine and needs to be installed on a Mac). Download mandelbrot.cu and the Makefile and run make all This will generate 3 programs:

Mandelbrot is a Mandelbrot set viewer designed for demonstrations . It allows you to zoom in and out and move around the Mandelbrot set. The controls are w for up, s for down, a for left, d for right, e to zoom in, q to zoom out and x to exit.

The executable named benchmark runs the computation without displaying anything and prints out the time it took before exiting.

XBenchmark is a hybrid that prints out the computation time and allows you to move around. This is useful because the computation time is dependent on your position within the Mandelbrot set.

Each of the programs takes between 0 and 4 commandline arguments

- the number of blocks used by the kernel

- the number of threads per block

- the image size in pixels, the image is always square

- the image depth (explained later)

What is the Mandelbrot set?¶

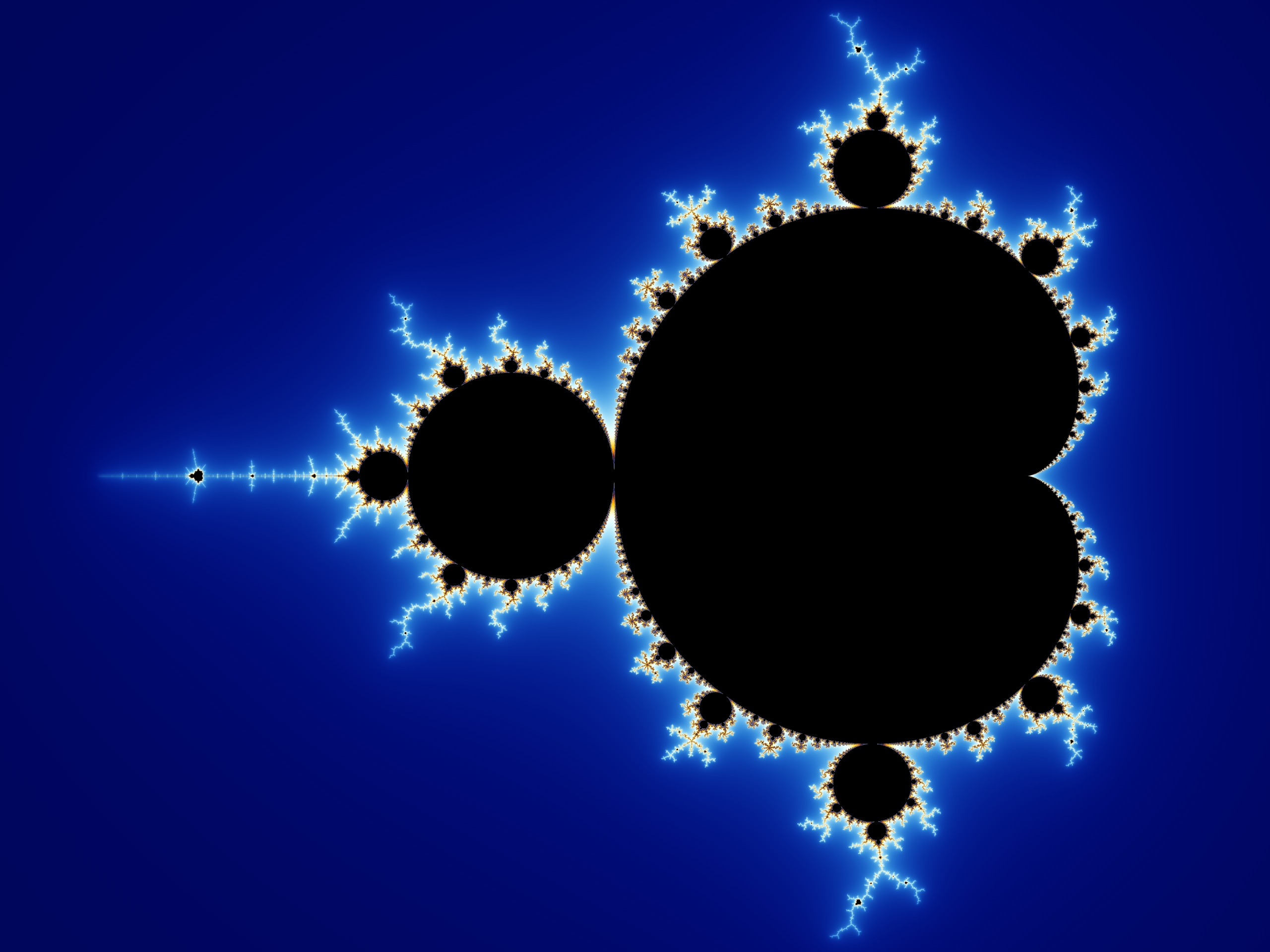

The Mandelbrot set is defined as the set of all complex numbers C such that the formula Zn+1 = Zn2 + C tends towards infinity. If we plot the real values of C on the X axis and the imaginary values of C on the Y axis we get a two dimensional fractal shape, such as this one created from running this code.

Coding the Mandelbrot set¶

The to determine whether a value is in or out of the Mandelbrot set we loop through the formula Zn+1 = Zn2 + C a certain number of times (this is the image depth from earlier) and during each iteration, check if the magnitude of Z is greater than 2; if so, we return false. However we want our Mandelbrot image to look pretty, so instead we’ll return the iteration in which it went out of bounds and and then interpret that number as a color. If it completes the loop without going out of bounds we’ll assign it the color black

After some algebraic manipulation to reduce the number of floating point multiplications, our code looks like this:

__device__ uint32_t mandel_double(double cr, double ci, int max_iter) {

double zr = 0;

double zi = 0;

double zrsqr = 0;

double zisqr = 0;

uint32_t i;

for (i = 0; i < max_iter; i++){

zi = zr * zi;

zi += zi;

zi += ci;

zr = zrsqr - zisqr + cr;

zrsqr = zr * zr;

zisqr = zi * zi;

//the fewer iterations it takes to diverge, the farther from the set

if (zrsqr + zisqr > 4.0) break;

}

return i;

}

Some notes about this CUDA code

- A function that is designed to be run on the GPU is designated with the special keyword __device__.

- The type uint32_t is an unsigned 32-bit integer declared in stdint.h.

- The variable max_iter is defaulted to be 100, and can be changed with the image depth command line argument.

But wait didn’t we say in the last chapter that conditionals should be avoided? Yes, when a thread returns early, it’s just dead weight in the warp, however due to the nature of the Mandelbrot set it is very likely that some warps have threads that all terminate before reaching max_iter so in some cases it will give us a slight speed up. If the warp contains a point within the Mandelbrot set, we won’t get any speed up from breaking.

We also need a kernel that will divide the pixels between the threads and run mandel_double on each of them Our code is as follows where dim is the image dimension, counts is the list representing our image, and step represents the distance between the points represented by the pixels:

__global__ void mandel_kernel(uint32_t *counts, double xmin, double ymin,

double step, int max_iter, int dim, uint32_t *colors) {

int pix_per_thread = dim * dim / (gridDim.x * blockDim.x);

int tId = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x;

int offset = pix_per_thread * tId;

for (int i = offset; i < offset + pix_per_thread; i++){

int x = i % dim;

int y = i / dim;

double cr = xmin + x * step;

double ci = ymin + y * step;

counts[y * dim + x] = colors[mandel_double(cr, ci, max_iter)];

}

if (gridDim.x * blockDim.x * pix_per_thread < dim * dim

&& tId < (dim * dim) - (blockDim.x * gridDim.x)){

int i = blockDim.x * gridDim.x * pix_per_thread + tId;

int x = i % dim;

int y = i / dim;

double cr = xmin + x * step;

double ci = ymin + y * step;

counts[y * dim + x] = colors[mandel_double(cr, ci, max_iter)];

}

}

Some notes about this CUDA code

- The keyword __global__ designates the kernel function.

- We execute the kernel function on the GPU device from main() like this, where n is the number of blocks of threads and ‘m’ is the number of threads per block:

mandel_kernel<<<n, m>>>(dev_counts, xmin , ymin, step, max_iter, dim, colors);

- In this case, the ‘tiling’ of the blocks of threads into a grid is a one-dimensional array of n blocks.

- Each thread calculates a particular value in the set based on its thread id (tId in the above code), which can be calculated using a data structure called blockDim, along with ones called blockIdx and threadIdx. The value blockDim.x gives us the total number of threads per block. The blockIdx.x value gives us the index of the block in which a particular thread running this code is located. Lastly, the threadIdx.x value is the index of this thread in its block. Thus, a thread running this code can uniquely identify itself with the computation blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x.

- We use blockDim.x when calculating the thread id above so that we could change the number of blocks, n, and the number of threads per block, m, programatically with command-line arguments and not have to change the kernel function.

In order to compensate for block and grid dimensions that do not easily divide the picture we make the first threads pick up the ‘slack.’ This is also the reason why we are not using 2 dimensional grids and blocks.

Warning

Always try to make your threads do the same amount of work. Scheduling extra work for some threads is inefficient since the other threads in the warp will have to wait for them to finish anyway. This code is purposefully messy so that it runs for any problem size.

That’s the meat of the program, feel free to explore the it on your own, most of the rest of the program is dedicated to displaying the data generated by these 2 functions.

In the next section, we will discuss how to choose the number of blocks and the number of threads per block in order to take maximum advantage of the GPU hardware.