CUDA Architecture¶

CPUs are designed to process as many sequential instructions as quickly as possible. While most CPUs support threading, creating a thread is usually an expensive operation and high-end CPUs can usually make efficient use of no more than about 12 concurrent threads.

GPUs on the other hand are designed to process a small number of parallel instructions on large sets of data as quickly as possible. For instance, calculating 1 million polygons and determining which to draw on the screen and where. To do this they rely on many slower processors and inexpensive threads.

Physical Architecture¶

CUDA-capable GPU cards are composed of one or more Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs), which are an abstraction of the underlying hardware. Each SM has a set of Streaming Processors (SPs), also called CUDA cores, which share a cache of shared memory that is faster than the GPU’s global memory but that can only be accessed by the threads running on the SPs the that SM. These streaming processors are the “cores” that execute instructions.

The numbers of SPs/cores in an SM and the number of SMs depend on your device: see the Finding your Device Specifications section below for details. It is important to realize, however, that regardless of GPU model, there are many more CUDA cores in a GPU than in a typical multicore CPU: hundreds or thousands more. For example, the Kepler Streaming Multiprocessor design, dubbed SMX, contains 192 single-precision CUDA cores, 64 double-precision units, 32 special function units, and 32 load/store units. (See the Kepler Architecture Whitepaper for a description and diagram.)

CUDA cores are grouped together to perform instructions in a what nVIDIA has termed a warp of threads. Warp simply means a group of threads that are scheduled together to execute the same instructions in lockstep. All CUDA cards to date use a warp size of 32. Each SM has at least one warp scheduler, which is responsible for executing 32 threads. Depending on the model of GPU, the cores may be double or quadruple pumped so that they execute one instruction on two or four threads in as many clock cycles. For instance, Tesla devices use a group of 8 quadpumped cores to execute a single warp. If there are less than 32 threads scheduled in the warp, it will still take as long to execute the instructions.

The CUDA programmer is responsible for ensuring that the threads are being assigned efficiently for code that is designed to run on the GPU. The assignment of threads is done virtually in the code using what is sometimes referred to as a ‘tiling’ scheme of blocks of threads that form a grid. Programmers define a kernel function that will be executed on the CUDA card using a particular tiling scheme.

Virtual Architecture¶

When programming in CUDA C we work with blocks of threads and grids of blocks. What is the relationship between this virtual architecture and the CUDA card’s physical architecture?

When kernels are launched, each block in a grid is assigned to a Streaming Multiprocessor. This allows threads in a block to use __shared__ memory. If a block doesn’t use the full resources of the SM then multiple blocks may be assigned at once. If all of the SMs are busy then the extra blocks will have to wait until a SM becomes free.

Once a block is assigned to an SM, it’s threads are split into warps by the warp scheduler and executed on the CUDA cores. Since the same instructions are executed on each thread in the warp simultaneously it’s generally a bad idea to have conditionals in kernel code. This type of code is sometimes called divergent: when some threads in a warp are unable to execute the same instruction as other threads in a warp, those threads are diverged and do no work.

Because a warp’s context (it’s registers, program counter etc.) stays on chip for the life of the warp, there is no additional cost to switching between warps vs executing the next step of a given warp. This allows the GPU to switch to hide some of it’s memory latency by switching to a new warp while it waits for a costly read.

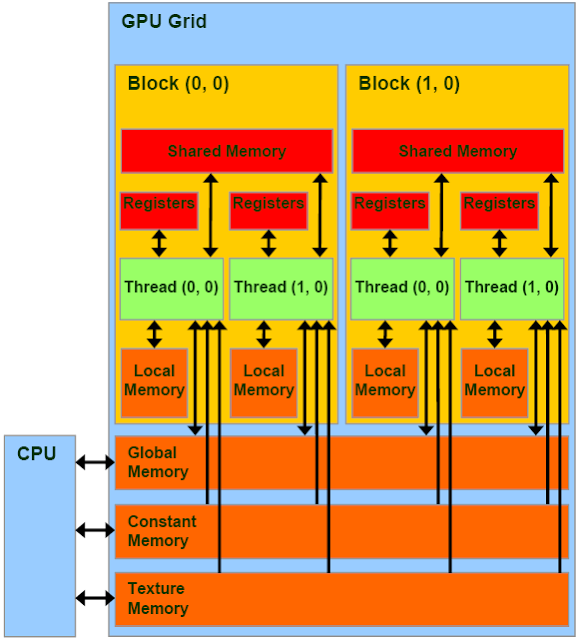

CUDA Memory¶

CUDA on chip memory is divided into several different regions

- Registers act the same way that registers on CPUs do, each

thread has it’s own set of registers.

- Local Memory local variables used by each thread. They are

not accessible by other threads even though they use the same L1 and L2 cache as global memory.

- Shared Memory is accessible by all threads in a block. It

must be declared using the __shared__ modifier. It has a higher bandwidth and lower latency than global memory. However, if multiple threads request the same address, the requests are processed serially, which slows down the application.

- Constant Memory is read-accessible by all threads and must

be declared with the __const__ modifier. In newer devices there is a separate read only constant cache.

- Global Memory is accessible by all threads. It’s the

slowest device memory, but on new cards, it is cached. Memory is pulled in 32, 64, or 128 byte memory transactions. Warps executing global memory accesses attempt to pull all the data from global memory simultaneously therefore it’s advantageous to use block sizes that are multiples of 32. If multidimensional arrays are used, it’s also advantageous to have the bounds padded so that they are multiples of 32

- Texture/Surface Memory is read-accesible by all threads, but

unlike Constant Memory, it is optimized for 2D spacial locality, and cache hits pull in surrounding values in both x and y directions.

CUDA Memory Hierarchy Image courtesy of NVIDIA

Finding your Device Specifications¶

nVIDIA provides a program with the installation of the CUDA developer toolkit that prints out the specifications of your device. To run it on a unix machine, execute this command:

/usr/local/cuda/samples/1_Utilities/deviceQuery/deviceQuery

If that doesn’t work you probably need to build the samples:

cd /usr/local/cuda/samples/1_Utilities/deviceQuery

sudo make

./deviceQuery

Look for the number of Multiprocessors on your device, the number of CUDA cores per SM, and the warp size.

The CUDA Toolkit with the samples is also available for Windows using Visual studio. See the excellent and thorough Getting Started Guide for Windows provided by nVIDIA for more information. However, some of the code described in the next section uses X11 calls for its graphical display, which will not easily run in Windows. You will need a package like Cygwin/X.